Chapter 4 – Public Space And The Istanbul Context

Public Spaces And The Building Of A Collective Identity

Polat and Dostoğlu refer to Arendt to describe “the term ‘public’ as everything that can be seen and heard by everybody, and as the world that is common to all of us…”.36 This definition resonates with the way spatial superstructures are described previously and it signifies the public space as a potential focus for placing the abstract concepts examined, in the material world. The public space appears as effective in imagining Schmidt’s definition of the movement space, or discovering the relationships between elements forming the space, or observing social structures, conflicts and negotiations.

Habermas, Sarah Lennox and Frank Lennox explain: “Public spaces and leisure activities [are] opening space for informality and experiential memory.”.37 Allowing the elements of the space to engage with each other in unpredictable, coincidental ways assists the construction of multiple narratives. They present the opportunity to proliferate the linear narratives which describes a single way of perceiving the space, introduce possibilities, options, and the extents of identity. By increasing the possibilities of micro negotiations which sustain the urban life, they contribute to the construction of urban resilience that specifically becomes valuable in crisis and conflicts.

Richard Sennett sees the spaces where the collective memories accumulate without the constraints of descriptive narratives, as opportunities to resolve problems and to heal. As he states: “people can indeed deal with the wounds of memory in their life histories only by remembering well […] Remembering well requires reopening wounds in a particular way, one which people cannot do by themselves; remembering well requires a social structure in which people can address others across the boundaries of difference. This is the liberal hope for collective memory. […] By sharing rather than privatizing memories, communities might find a way to tell the truth about themselves.”.38 In other words, they can discover or agree on the definition of their identities. Since public spaces provide the environment for collective identity to develop independently and vigorously, they provide an accepting spatial context that results in an inclusive shared identity.

In line with Sennett’s approach, Habermas defines the public space as “a social sphere where a public viewpoint can be produced and picked up by all.”.39 In a spatial context that includes many ethnicities, religions, and languages, the manner described by Habermas becomes critical to provide sustainability. By adopting this perspective, recognizing all parties constructing a space becomes a possibility. This approach allows the negotiations to take place and the participants to agree on a shared future and a shared identity. Public space sustains this by the providing the continuity of micro-discussions on incalculable matters.

Mentioned interactions and attributes of public space emerge as critical issues in the context of Istanbul which is multi-layered and conflicted in sustaining urban dialogues. Therefore, this study probes public leisure space examples as they act as a catalyst to solve conflicts and build collective memories and investigates the ways people managed to stay together and negotiate the space in Istanbul before. The two typologies researched are chosen based on being scenes for informal place-making practices. Although they can be described as spatial typologies, they also are free topographies for people to appropriate, temporarily occupy and leave by erasing their traces. They are created and dismantled within short visits and become a part of the intangible, collectively created memory of a space.

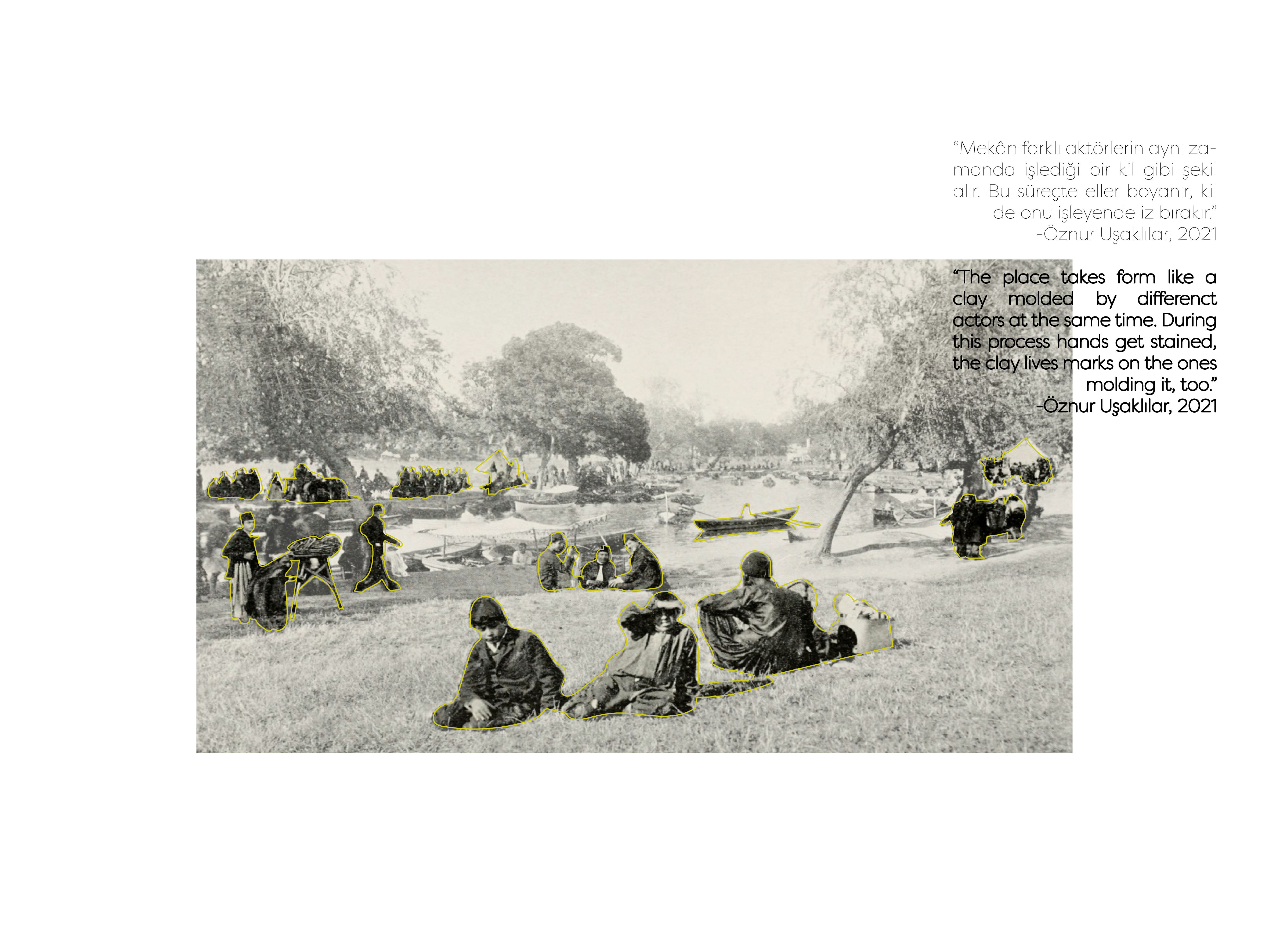

[Figure 7] - Space Formed by Experience (quote: Öznur Uşaklılar [2])

[Figure 7] - Space Formed by Experience (quote: Öznur Uşaklılar [2])Discovering Istanbul’s Public Space

Istanbul has a unique landscape due to the sea passing through the city by dividing it into two. The citizens’ relationship with this body of water creates curious circumstances on the shores and the hilly terrain causes introversive villages to form on the valleys; generating different ways of occupying the geography. The attempts of recognizing the city as a whole and bringing these unique ways of developed under a “Istanbul typology” becomes a challenge. On the other hand, these varying urban practices produce alternative way of representing the spatial perception which take place simultaneously and overlap in interesting ways.

Alternating practices produce narratives differing from each other due to reinterpretations by various identities. While sharing the stories of spatial experiences, ‘performers’ create their own version and the audience understand them in their own unique ways. In a reciprocal, interactive exchange of knowledge, the shared stories pass from one to another with minimal transformations, like Chinese whispers. For example, a Muslim woman tells the ‘same’ story different than a Jewish child. When these alternating stories overlap, certain elements repeated in each version suggest a core and it becomes a part of the abstract layer of the space stands ready to be reinterpreted.

Creating the common core of the narratives, the shared identities distilled from the collective memory, roots in the complex privacy-publicity relations in the city. In Istanbul, private life is not disconnected from the public life and invasions of the public space are common. The proposed ways of occupying the space by design are almost never followed. The manifestations of lifestyles in the common spaces define the public spheres. In İstanbul, this aspect becomes the most characteristic attribute.

As Deniz Güner states, in Turkey (and Istanbul), “in discordance with the definitions in Western Europe, the relationship between the privacy and the publicity is not dependent on dualities […], instead, a rather permeable and ubiquitous structure can be noticed. […] The leisure spaces, whose boundaries are uncertain and where gradual transition between privacy and publicity is visible, can only be explained through a sovereignty metaphor describing the areas as transitory zones with borders that cannot be drawn. On the other hand, these leisure spaces with undefined and unclear borders can be recognized as public by the society, only if the social practices and rituals of coming together happening here accumulate in mental cartographies of the citizen.”.40 In this sense, the public spaces in Istanbul can be realized as free spaces left open for appropriations and gain meaning through occupation and the perception of them in a certain way. The case studies picked, reflect these spatial concepts and characteristics.

36 Polat, Sibel, and Neslihan Dostoglu. ‘Measuring Place Identity in Public Open Spaces’. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Urban Design and Planning 170 (15 February 2016): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1680/jurdp.15.00031.

37 Habermas, Jürgen, Sara Lennox, and Frank Lennox. ‘The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964)’. New German Critique, no. 3 (1974): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/487737.

38 Sennett, Richard. ‘From “Disturbing Memories”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 284. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

39 Habermas, Jürgen, Sara Lennox, and Frank Lennox. op. cit.

40 Deniz Güner. ‘Istanbul Kıyı Alanlarında Değişen Kamusallıklar’. Accessed 22 July 2022. https://archplus.net/de/istanbul-kiyi-alanlarinda-degisen-kamusalliklar/.