Chapter 3 – The Theoretical Framework

The following chapter will set the theoretical framework for this study by investigating the relationships between memory, spatial perception and identity. The discussion will begin by presenting the literary research on memory’s relationship with the identity. Moving forward, the memory-identity relationship will be put in a spatial context by probing the ways we perceive and recall the space-time. Then, various perspectives on identity’s definition will be presented and its uncertainty within an everchanging space will be explored. Finally, the outcomes of this literary research will be discussed and put in a spatial-theoretical framework which is represented in two physical model complimenting this study and explained in following sections. The aim is to understand how identity conflicts reflect on or dwell on the spatial experience and how the relationships between the studied concepts construct social structures. By doing so, a theoretical approach will be developed for probing the case studies’ part in providing social cohesion and building a collective memory and identity.

Identity and The Past

According to Edward Casey, commemoration is a participatory act that is based on “intensified remembering”.10 As a memory is commemorated, the elements surrounding that memory becomes superposed in an alternative dimension and a new phenomenon is created.11 As the contemplations on a memory start, a past incident that is considered full-circle and solid, breaks into its essential parts and becomes “alive in the minds and bodies of commemorators”.12 This process, as Casey states, concludes in the creation of a ‘metaphysical superstructure of memory’13: an invented, cumulative, descriptive phenomenon, an identity.

Similar to Casey, Jeffrey K. Olick recognizes the process of remembering as social and relational. He explains that the collective act of remembering can be probed via two perspectives. The first as an individualistic act of remembering that takes place in a social network; the second as the commemoration that is practiced with others over shared meanings of subjects and mnemonic tools.14 The first perspective can be found similar to Casey’s previously explained approach that defines a collectively constructed memory. It argues that individuals remember and make sense of a memory based on their own perception, background, and individual identity while the hierarchies and power relations between them determine the louder, more visible interpretations and create social identities. The second perspective Olick suggests portrays the elements of memory in a more static manner when compared to the first. According to this, the elements become meaningful either based on contemporary values and concerns that are created by behavioural or ideological patterns; or based on mnemonic practices and tools such as remembering by muscle memory.15 Summing up his approach, the process of recollection that happens while revisiting a memory, can be seen as an act of learning, naming, and understanding the elements constituting the memory and making sense of surroundings based on the accumulated knowledge of the past. The practical actualization of this recollection process in a collective setting, which can be better understood by probing Hobsbawm’s point of view that connects identity and space-time with rituals and spatial practices.

As explained by Hobsbawm; conventions, routines, and rituals form traditions by repetition.16 In this sense, traditions can be interpreted in two ways. First, as an attitude: an act of making prioritizations between the aspects creating the space-time and selecting some aspects to be repeated or continued. From this perspective, the traditions necessarily contain a subjective layer and a hierarchy. Second; as concretized, almost tangible, and sometimes actually tangible interpretations of emotions, thoughts, actions, or objects constructing the space-time. Via intentional or unintentional processes, some aspects of the space-time become mnemonic tools that represent and build identities simultaneously. When put together these approaches and mnemonic elements form a complex and unpredictable nexus that describes the space identity based on the duality between being an attitude and a set of abstract or solid elements. The ubiquity suggested while defining the identity resonates in the way space is experienced, too.

Spatial Perception And Narratives

According to Pallasmaa, “the quality of a space or place is not merely a visual perceptual quality as it is usually assumed. The judgement of environmental character is a complex multi-sensory fusion of countless factors which are immediately and synthetically grasped as an overall atmosphere, ambience, feeling or mood.”.17 Therefore, the space can be realized as a ubiquitous concept, reciprocally constructing and being constructed by the experiencer and her interactions with the space via multiple senses. These multisensory interactions are especially significant for understanding the space perception while looking from a Deleuzo-Spinozist perspective. According to it, the relationship between the elements of a space can be observed as non-linear; meaning that the elements interact with each other in unpredictable and undirect ways while building the space as a phenomenon.18 Nevertheless, thee interactions and elements also share a common attribute: during the experience, they simultaneously become the input and the output of the space perception. This means that the elements creating the space gain new meanings as they are perceived, and these meanings become the new elements for further interpretations. Within this reciprocal process which can be described as ‘perception’, the space gains multiple subjective definitions and becomes the place.

Ulrik Schmidt’s explanation of space perception aligns with the approach taken here to understand the process of space becoming the place. As he states, the space is ambient.19 During the experience of it, the space -with its tangible intangible elements- surrounds the experiencing body. While doing so, it stays as a ubiquitous, ever-changing concept: “all heterogenous elements and dimensions connect or mix in a synthesizing, univocal production” that is radically dynamic.20 As the space is perceived, the “sensory scope expand[s]”;21 the realization of the perception goes beyond sensing the physical space. In this process, the space is epistemologically and emotionally understood and acknowledged as a whole. Additionally, the perception indicates a ‘detached presence’ between the space and its observers: their participation in the space experience happens similar to a passenger’s.22 This aspect of perception can be imagined like walking in a very crowded street. In which case having a general understanding of the surroundings is possible but the experience lacks the opportunity to capture the full details. Consequently, the perceiver becomes a transiting, temporary aspect in the space and the “perception” becomes a dynamic, ambient, uncertain concept or act.

Identity As A Dynamic Phenomenon

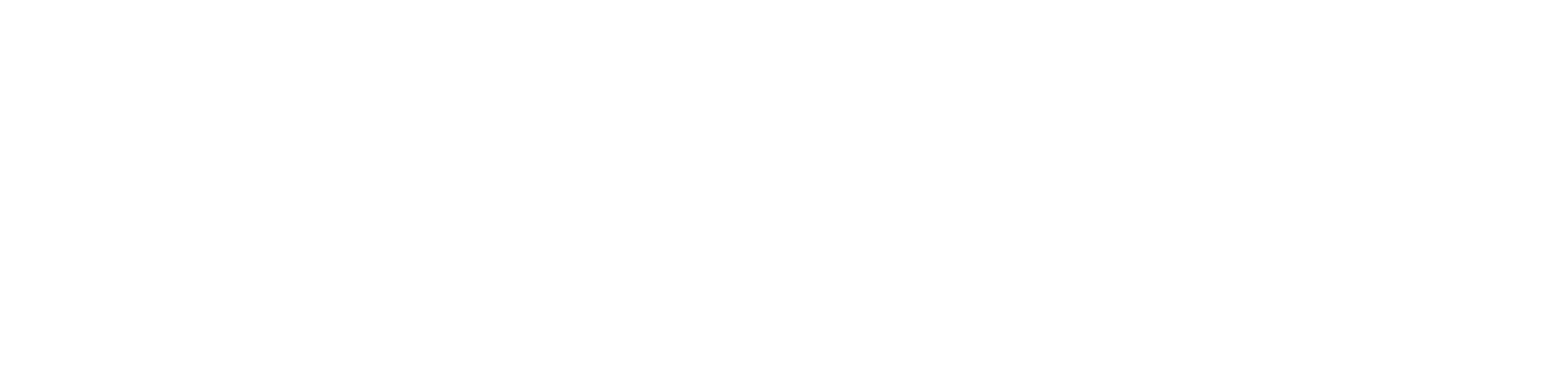

[Figure 4] - Identity oscillates between historical narratives and memory

According to different researchers, the distinction between “memory” and “history” carry a significant importance while understanding how the identity phenomenon is constructed through the perceptions and commemorations of space-time. From a perspective that recognizes the space and the memory as cumulative entities; the elements of a space define identities, while they gain meaning through perception. Having said that, from a perspective that recognizes the time and the space as linear structures, which can be named as “historicizing” the past, the historical narratives indicate clearly defined identities by suggesting organized, consistent and convincing stories. As Confino mentions, the politics of memory starts at this point: when the memory is considered as the “subjective experience of a group that essentially sustains a relationship of power”, the way a past story indicates an identity necessarily becomes an issue of narration, an issue of “who wants whom to remember what, and why”.23 Historicizing the past by narrating a space experience amplifies a certain way of understanding of the past and describes a certain memory amongst the others as the truth, the only possible perception. As the result, the multi-layered and cloud-like gatherings of various perceptions forming a memory, becomes fitted in singular narratives that are called as the ‘history’, as Megill puts it down: “a pseudo-objective discourse”.24

As Samuel states, the heritage [the memory and space] which is an “expressive totality, a seamless web, [...] is conceptualized as systemic” by being narrated: “projecting a unified set of meanings which are impervious to challenge.”.25 Accordingly, the cultural identity, or heritage as Samuel put, which is summarized and concretized in a single line story becomes closed to discussion. These narratives with a theme, an aim; a beginning and an end, portray suggested identities and doesnot leave room for individuals’ interpretations and spontaneity. Here, the conflicts between individual interpretations of space-time that collectively build an identity and the coherent narratives describing static identities begin.

As Megill states: “Since historical particularism is often articulated in the language of memory, a tension is set up between history and memory. On the other hand, ‘history’ appears as a pseudo-objective discourse that rides roughshod over particular memories and identities, which claim to have an experiential reality and authenticity that history lacks. On the other hand, memory appears as an unmeasured discourse that, in the service of desire, makes claims for its own validity that cannot be justified.”26 On behalf of the history, a narrated, consistent story can contribute to providing a sense of safety and comfort and unite people under the concepts it provides. Ernest Renan explains these concepts in “What is a Nation?”.

Based on Renan’s text, a common language, or a shared geographical spot can be uniting but as he states: “[m]ore valuable by far than common customs posts and frontiers conforming to strategic ideas is the fact of sharing, in the past, a glorious heritage and regrets, and of having, in the future, [a shared] programme to put into effect, or the fact of having suffered, enjoyed, and hoped together. These are the kinds of things that can be understood in spite of differences of race and language […] ‘having suffered together’ and, indeed, suffering in common unifies more than joy does.”.27 Renan’s elaborations on the ways nations form, examplifies the ways historical narratives develop and create nations. They also make Svetlana Boym’s conceptualization of nostalgia significant and helps understanding the concept of “restorative nostalgia” introduced by her and how it becomes effective in creating alternative futures. 28

Nostalgia can be understood as the longing for a memory. Similar to ‘identity’, this feeling may gain different meanings when it is approached from the two perspectives described before on space-time perception. From the “linear time” perspective, the memories of common sufferings, idealized futures, or ‘better’ pasts can be longed for. Nevertheless, this feeling gains a more complicated meaning, when approached from the other perspective, accepting the space-time as a nexus or a collective ubiquitous entity. In this case, the elements creating the space and their interactions become the memories themselves and altogether create the identity. When a piece from the complex identity is disfigured, the longing felt for this lost element resembles the loss of a part of one’s physical body and resonates as a conflict of identity.29 Svetlana Boym defines “reflective nostalgia” similar to this feeling of irritation: a controversy relating the identity.30 If this feeling is felt for future longings -if what is missed is a possible memory or identity; then this feeling can be considered as “restorative nostalgia” and it can be used as a productive tool to imagine alternative identities and space-time structures. While this type of nostalgia can become a beneficial virtue, the ways and reasons for creating these are questionable in terms of why, by who, and for whom they are created for as Burke pointed out.31

Overall, as Megill states a ‘common feature32, as Renan states as a ‘common suffering, a shared trauma, a language or a belief system’33 can be uniting. A commonality shared with other individuals can suggest a feeling of belonging, a description of self within a social structure and silence the annoying ambiguity. Suggested overarching narratives have the power to offer perspectives of rendering memories in a certain way -as definitive, clear, and static identities- and they can be tools to comprehend, categorize and make sense of our surroundings. Therefore, belonging to a social group, defining oneself using the tools suggested by singularly narrated pasts can become increasingly attractive as the struggles regarding the identity increases. A ‘grand history’ indicating a consistent identity can become a reference point, an instructions manual to calm down: to locate oneself in an actually complicated and complex network and to dim the voices of a self-destructive anxiety. In the end, as Megill suggests: “when identity becomes uncertain, memory rises in value”.34 Nevertheless, this discussion gets stuck in the question of who’s memory to refer and if it is inclusive of each of us.

As Megill contintues, “…The boundaries between history and memory nonetheless cannot be precisely established, [...] in the absence of a single, unquestioned authority or framework, the tension between history and memory cannot be resolved. […] Thus it is hard to know how the tension between the historical and the mnemonic can ever be overcome. It is certain that the sum of memories does not add up to history. It is equally certain that history does not by itself generate a collective consciousness, an identity, and that when it gets involved in projects of identity-formation and promotion, trouble results. Thus a boundary remains between history and memory that we can cross from time to time but that we cannot, and should not wish to, eliminate.”35 Summing up his thoughts, it can be said that the past can be interpreted differently as it is acknowledged through memories or histories, and the identity can actually be welcomed as a dynamic phenomenon moving between linearly narrated histories and cloud-like memory superstructures.

Discussion

In the literature research the relationships between memory, identity, and the spatial perception are examined by introducing different perspectives and discussions on the topics. The relationships between these concepts are investigated via three approaches based on three takeaways. Firstly, identity is found to be in relation with the ways memories are remembered and this correlation is explored through social and spatial perspectives. Secondly, the space is realized as an everchanging, ubiquitous concept and by looking at the physical and intellectual practices, the space perception and the approaches towards narrating this experience are discovered. The differences between the narration of space and its genuine experience are questioned and the way the users engage with the surrounding space and its memory is redefined. Thirdly, the definitions of identity based on its relationship with memory, space, and their narrations are examined: the concepts of memory and history are discussed, and the identity is defined in this framework as a dynamic concept. In the following discussion, these outcomes will be explained and an abstract spatial-theoretical framework will be portrayed.

Dwelling on the literature research, the memories can be acknowledged as building blocks of individual and collective identities. They can be described asphenomena being formed as a space turns into a place by being perceived at a certain time, by a certain someone. In this sense they can be seen as multi-layered abstract constructs coming into existence in an intangible dimension by merging: the realizations of a physical space, the interactions between the physical elements creating this space (which indicate a reference to time) and abstract senses, meanings and emotions they evoke in the mind of a subjective experiencing body. By definition, an understanding of the memory as such appears to be spatial; but as critical for this study, it also has a social layer. Since this definition explains a single memory of a certain participant, it may be clear and easy to understand. However, when the totality of a spatial context is imagined; it is possible to realize that multiple participants, multiple memories and multiple states of a physical space clash and stand together. Therefore, it can be said that the aforementioned superstructure of the memory contains various meanings and references by the multiple experiences of a transforming physical spatiality.

Although during a personal experience the meaning of space could be consistent and as narrow as an individual’s understanding of it, it is still not singular since the elements of the perceived space is relational. All different experiences of a space -memories- stand and occur in a nexus connecting them with the others. In this context, the accumulation of an individual’s spatial experiences (which by definition include a physical reality, a series of interactions -behaviour, and an abstract reality – thoughts, emotions and senses) can be defined as her individual identity. Building on this, the complex spatial context where these experiences clash and form a nexus, can be defined as the collective memory – a collective identity. As a consequence of these definitions, this study bases collective identity on spatial practices and their intellectual, sensory and emotional meanings. Therefore, the collective identity defined here is in deep relation with culture of occupying a space.

With this approach, the ways different experiences bond with each other in a spatial context, define shared identities and how conflicts or harmonies form between individual identities. The relationship between the individual identity, collective identity and the spatial experience -in other words the memory- can be defined in this way. However, this definition stays short in discussing the way we recognize and recall our surroundings, and different identities in practice during an experience or within the inevitable social constructs such as hierarchal power relations or communities formed based on shared languages, backgrounds, or physical attributes. To be able to move forward we need to probe the ways spatial experiences are narrated and how these narrations are associated with genuine experiences of a physical space - which are explained as profoundly in touch with the individual and collective identities previously.

Based on the studies probed in the literature research, the experience of a of a space, the space-time can be described as an uncertain, ambient, cloud-like entity which is in constant transformation. From this perspective, as Schmidt explains, the way one experiences the space can be found similar to a heightened experience example, a fast-train journey where it is possible to capture only parts of the complex network surrounding one and to have a sense that there is more to see, feel, learn, and understand but not being able to grasp the full material. Similarly, while looking at the complicated networks with the aim of narrating them, we stay restricted with our perceptive limits and feel obligated to set a perspective and a framework to be able convey what could be processed. Therefore, while constructing a historical narrative to describe a spatial experience, some of the elements standing in the nexus of the spatial superstructure are prioritized and picked out of their context. They are then put in a linear (frequently cause-and-effect relationship) that completes a consistent story. Since this is an inevitably subjective the process, the narration of a real or an imagined spatial experience becomes bound to be biased.

As priorities are set, and events are listed based on the observer’s previous knowledge, subjectivity, or other pragmatic agendas; complex communities, great disasters or curious inventions are presented as summaries and turn into details in the woven fabric - a linear narrative, a story. Although the experience’s relational, multi-layered, multi-sensorial, and uncertain nature does not change, the time is rationalised by being put down in a narrational method. It adequately captures a way of relating two consecutive events. The work done here can be explained as reorganising the spatial elements: taking them out of their spatial context and simplifying the complex relationships they have with others, and creating a continuous, easy-to-understand line of events. Given that the consequences of these kind of narrations are questionable, the fact here is that the coincidental elements of a space -minor reactions and interactions such as family fights, mimics, small gestures, love stories, funerals or maybe relatively casual dinners that carry beyond negligible weight in the totality of the space- are insufficiently recognized while telling an ‘over-arching’ story.

The critical part of this discussion lies in the fact that the linearly structured historical narratives describe identities as static and clearly defined which is not in line with the genuine experience of the space. When studied from bottom-up, by summing up the previous section, the participants and commemorators become present in a space as social beings since the bonds between them and the elements of the space and memory reproduce and gained different meanings. When pictured visually, during commemoration or perception each element, incident, or idea belonging to this space or memory becomes repositioned in a nexus that links each one to another. Consequently, the boundaries of time break. The elements constituting the memory gain significance beyond a restricted timeframe. This way, the links between today and the past are built and together they signify a “definition across space-time”: an identity that is not finite, that is in constant transformation and reproduced by each interaction and new interpretation.

Contrarily, the linear narratives are capable of telling a singular interpretation and, as previously suggested, they define clear-cut identities. Due to their formation based on selective narration, they cannot be fully inclusive. They also cannot claim to be dynamic or objective. The concretized identities constructed by picking certain elements from uncertain memory clouds appears as a necessarily subjective process. Moreover, the aim to construct a consistent historical narrative itself, suggests a political stance or a certain ideology even if it occurs to be unintentional. Although, the narratives are derived from the interpretation based on the elements and interactions within a space or, even though they become elements of the same spatial context as becoming a part of the abstract layer; the non-dynamic and categorical descriptions narratives identify inorganically weigh more in complex superstructures and silence others via power relations.

![]()

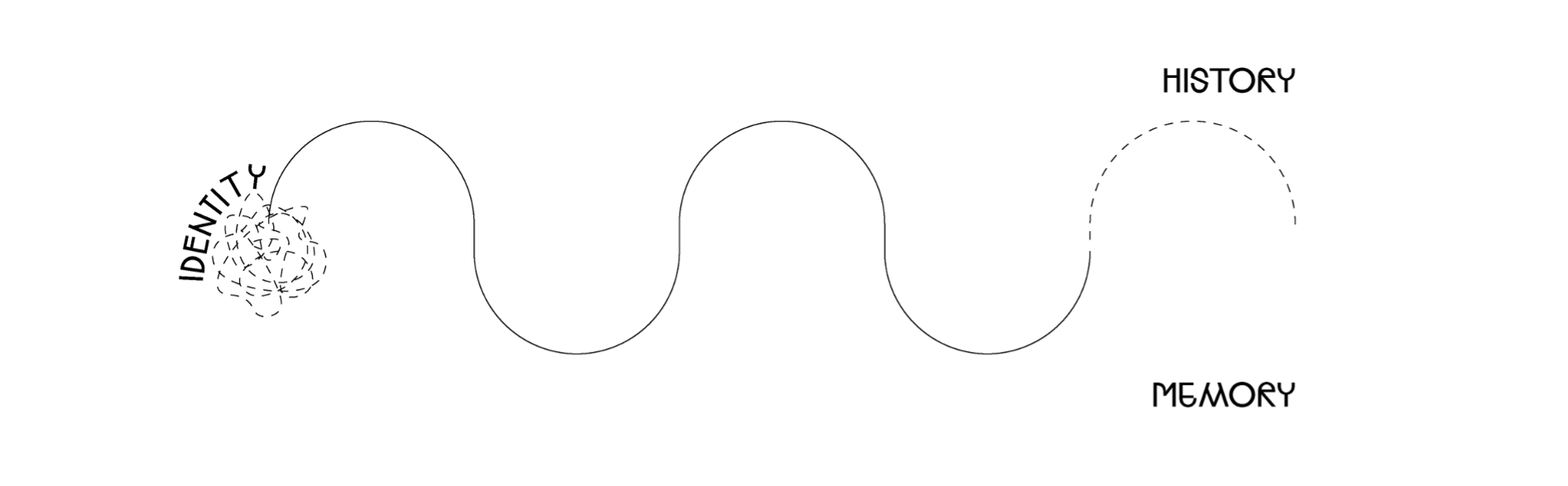

[Figure 5] - Memory - History

On the other hand, when the last section of the literature review is taken as a reference, the linear narratives and static identity definitions appear to be useful especially in conflicted social circumstances. Confusion and disorientation in complex situations, similar to the feelings felt by a person with amnesia or Alzheimer’s disease, can be cured by recognizing a familiar aspect from one’s memory, which can help making sense of one’s surroundings. In the lack of this, or when there are conflicts about identity, a suggested static and defined identity can be a tool teach one how to respond and tackle or bypass identity conflicts. Trust and safety can be provided via familiarity and consistency, although embracing the complexities of an individual identity and multiple identities becomes an issue in this case.

In summary, different ways of narrating the memory and recognizing identities have different perks which become beneficial depending on changing spatial-social circumstances. Therefore, the identity -as a phenomenon that is accepted in this research as an everchanging entity- and the definition of a collective memory constantly oscillates between what is described by linear narratives and what is produced by the spatial experience. To suggest an inclusive spatial perspective and to discover possibilities of acknowledging all possible elements that take part in structuring the spatial superstructures, this study offers the investigation of shared identities through a non-linear approach acknowledging the ubiquitous and cumulative space phenomenon. This way, it aims to challenge the social polarization; recognize collectively formed memory superstructures (collective identities) and explore ways to non-hierarchally visualize these abstract concepts. So, how can we imagine the space to the extents of its complexity? How can we recognize and visualize the collective identity as organic, non-hierarchal, ever-changing entities beyond defining narratives? To answer these questions, spatial contexts that may present prolific complex interactions between its elements are investigated. As a result, public leisure spaces are identified as auspicious settings that may have a lot to offer in terms of building identities and resolving social conflicts and polarization.

10 Edward Casey. ‘From Remembering: A Phenomenological Study’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 187. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

11 Edward Casey. ‘From Remembering: A Phenomenological Study’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 186. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

12 ibid.

13 ibid.

14 Jeffrey K. Olick. ‘From “ Collective Memory: The Two Cultures”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 225–228. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

15 ibid.

16 Eric Hobsbawm. ‘From “Introduction: Inventing Traditions”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 271–74. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

17 Pallasmaa, Juhani. ‘Space, place and atmosphere. Emotion and peripherical perception in architectural experience’. Lebenswelt. Aesthetics and philosophy of experience., no. 4 (7 July 2014): 230. https://doi.org/10.13130/2240-9599/4202.

18 Gatens, Moira. ‘Feminism as “Password”: Re-Thinking the “Possible” with Spinoza and Deleuze’. Hypatia 15, no. 2 (2000): 63.

19 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 26–39. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

20 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 31–32. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

21 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 33. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

22 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 33–35. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

23 Confino, Alon. ‘From “ Collective Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 198. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

24 Megill, Allan. ‘From “History, Memory, Identity”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 193. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

25 Samuel, Raphael. ‘From “Theaters of Memory”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 261–64. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

26 Megill, op. cit.

27 Ernest Renan. Extract from from ‘What Is a Nation’. p. 83.

28 Svetlana Boym. ‘From “Nostalgia and Its Discontents”’. The Collective Memory Reader, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 452-57.

29 ibid.

30 ibid.

31 Peter Burke. ‘From “History as Social Memory”’. The Collective Memory Reader, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 188-92.

32 Megill, op. cit.

33 Renan, op. cit.

34 Megill, op. cit.

35 Megill, op. cit.

In the literature research the relationships between memory, identity, and the spatial perception are examined by introducing different perspectives and discussions on the topics. The relationships between these concepts are investigated via three approaches based on three takeaways. Firstly, identity is found to be in relation with the ways memories are remembered and this correlation is explored through social and spatial perspectives. Secondly, the space is realized as an everchanging, ubiquitous concept and by looking at the physical and intellectual practices, the space perception and the approaches towards narrating this experience are discovered. The differences between the narration of space and its genuine experience are questioned and the way the users engage with the surrounding space and its memory is redefined. Thirdly, the definitions of identity based on its relationship with memory, space, and their narrations are examined: the concepts of memory and history are discussed, and the identity is defined in this framework as a dynamic concept. In the following discussion, these outcomes will be explained and an abstract spatial-theoretical framework will be portrayed.

Dwelling on the literature research, the memories can be acknowledged as building blocks of individual and collective identities. They can be described asphenomena being formed as a space turns into a place by being perceived at a certain time, by a certain someone. In this sense they can be seen as multi-layered abstract constructs coming into existence in an intangible dimension by merging: the realizations of a physical space, the interactions between the physical elements creating this space (which indicate a reference to time) and abstract senses, meanings and emotions they evoke in the mind of a subjective experiencing body. By definition, an understanding of the memory as such appears to be spatial; but as critical for this study, it also has a social layer. Since this definition explains a single memory of a certain participant, it may be clear and easy to understand. However, when the totality of a spatial context is imagined; it is possible to realize that multiple participants, multiple memories and multiple states of a physical space clash and stand together. Therefore, it can be said that the aforementioned superstructure of the memory contains various meanings and references by the multiple experiences of a transforming physical spatiality.

Although during a personal experience the meaning of space could be consistent and as narrow as an individual’s understanding of it, it is still not singular since the elements of the perceived space is relational. All different experiences of a space -memories- stand and occur in a nexus connecting them with the others. In this context, the accumulation of an individual’s spatial experiences (which by definition include a physical reality, a series of interactions -behaviour, and an abstract reality – thoughts, emotions and senses) can be defined as her individual identity. Building on this, the complex spatial context where these experiences clash and form a nexus, can be defined as the collective memory – a collective identity. As a consequence of these definitions, this study bases collective identity on spatial practices and their intellectual, sensory and emotional meanings. Therefore, the collective identity defined here is in deep relation with culture of occupying a space.

With this approach, the ways different experiences bond with each other in a spatial context, define shared identities and how conflicts or harmonies form between individual identities. The relationship between the individual identity, collective identity and the spatial experience -in other words the memory- can be defined in this way. However, this definition stays short in discussing the way we recognize and recall our surroundings, and different identities in practice during an experience or within the inevitable social constructs such as hierarchal power relations or communities formed based on shared languages, backgrounds, or physical attributes. To be able to move forward we need to probe the ways spatial experiences are narrated and how these narrations are associated with genuine experiences of a physical space - which are explained as profoundly in touch with the individual and collective identities previously.

Based on the studies probed in the literature research, the experience of a of a space, the space-time can be described as an uncertain, ambient, cloud-like entity which is in constant transformation. From this perspective, as Schmidt explains, the way one experiences the space can be found similar to a heightened experience example, a fast-train journey where it is possible to capture only parts of the complex network surrounding one and to have a sense that there is more to see, feel, learn, and understand but not being able to grasp the full material. Similarly, while looking at the complicated networks with the aim of narrating them, we stay restricted with our perceptive limits and feel obligated to set a perspective and a framework to be able convey what could be processed. Therefore, while constructing a historical narrative to describe a spatial experience, some of the elements standing in the nexus of the spatial superstructure are prioritized and picked out of their context. They are then put in a linear (frequently cause-and-effect relationship) that completes a consistent story. Since this is an inevitably subjective the process, the narration of a real or an imagined spatial experience becomes bound to be biased.

As priorities are set, and events are listed based on the observer’s previous knowledge, subjectivity, or other pragmatic agendas; complex communities, great disasters or curious inventions are presented as summaries and turn into details in the woven fabric - a linear narrative, a story. Although the experience’s relational, multi-layered, multi-sensorial, and uncertain nature does not change, the time is rationalised by being put down in a narrational method. It adequately captures a way of relating two consecutive events. The work done here can be explained as reorganising the spatial elements: taking them out of their spatial context and simplifying the complex relationships they have with others, and creating a continuous, easy-to-understand line of events. Given that the consequences of these kind of narrations are questionable, the fact here is that the coincidental elements of a space -minor reactions and interactions such as family fights, mimics, small gestures, love stories, funerals or maybe relatively casual dinners that carry beyond negligible weight in the totality of the space- are insufficiently recognized while telling an ‘over-arching’ story.

The critical part of this discussion lies in the fact that the linearly structured historical narratives describe identities as static and clearly defined which is not in line with the genuine experience of the space. When studied from bottom-up, by summing up the previous section, the participants and commemorators become present in a space as social beings since the bonds between them and the elements of the space and memory reproduce and gained different meanings. When pictured visually, during commemoration or perception each element, incident, or idea belonging to this space or memory becomes repositioned in a nexus that links each one to another. Consequently, the boundaries of time break. The elements constituting the memory gain significance beyond a restricted timeframe. This way, the links between today and the past are built and together they signify a “definition across space-time”: an identity that is not finite, that is in constant transformation and reproduced by each interaction and new interpretation.

Contrarily, the linear narratives are capable of telling a singular interpretation and, as previously suggested, they define clear-cut identities. Due to their formation based on selective narration, they cannot be fully inclusive. They also cannot claim to be dynamic or objective. The concretized identities constructed by picking certain elements from uncertain memory clouds appears as a necessarily subjective process. Moreover, the aim to construct a consistent historical narrative itself, suggests a political stance or a certain ideology even if it occurs to be unintentional. Although, the narratives are derived from the interpretation based on the elements and interactions within a space or, even though they become elements of the same spatial context as becoming a part of the abstract layer; the non-dynamic and categorical descriptions narratives identify inorganically weigh more in complex superstructures and silence others via power relations.

[Figure 5] - Memory - History

On the other hand, when the last section of the literature review is taken as a reference, the linear narratives and static identity definitions appear to be useful especially in conflicted social circumstances. Confusion and disorientation in complex situations, similar to the feelings felt by a person with amnesia or Alzheimer’s disease, can be cured by recognizing a familiar aspect from one’s memory, which can help making sense of one’s surroundings. In the lack of this, or when there are conflicts about identity, a suggested static and defined identity can be a tool teach one how to respond and tackle or bypass identity conflicts. Trust and safety can be provided via familiarity and consistency, although embracing the complexities of an individual identity and multiple identities becomes an issue in this case.

In summary, different ways of narrating the memory and recognizing identities have different perks which become beneficial depending on changing spatial-social circumstances. Therefore, the identity -as a phenomenon that is accepted in this research as an everchanging entity- and the definition of a collective memory constantly oscillates between what is described by linear narratives and what is produced by the spatial experience. To suggest an inclusive spatial perspective and to discover possibilities of acknowledging all possible elements that take part in structuring the spatial superstructures, this study offers the investigation of shared identities through a non-linear approach acknowledging the ubiquitous and cumulative space phenomenon. This way, it aims to challenge the social polarization; recognize collectively formed memory superstructures (collective identities) and explore ways to non-hierarchally visualize these abstract concepts. So, how can we imagine the space to the extents of its complexity? How can we recognize and visualize the collective identity as organic, non-hierarchal, ever-changing entities beyond defining narratives? To answer these questions, spatial contexts that may present prolific complex interactions between its elements are investigated. As a result, public leisure spaces are identified as auspicious settings that may have a lot to offer in terms of building identities and resolving social conflicts and polarization.

10 Edward Casey. ‘From Remembering: A Phenomenological Study’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 187. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

11 Edward Casey. ‘From Remembering: A Phenomenological Study’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 186. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

12 ibid.

13 ibid.

14 Jeffrey K. Olick. ‘From “ Collective Memory: The Two Cultures”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 225–228. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

15 ibid.

16 Eric Hobsbawm. ‘From “Introduction: Inventing Traditions”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 271–74. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

17 Pallasmaa, Juhani. ‘Space, place and atmosphere. Emotion and peripherical perception in architectural experience’. Lebenswelt. Aesthetics and philosophy of experience., no. 4 (7 July 2014): 230. https://doi.org/10.13130/2240-9599/4202.

18 Gatens, Moira. ‘Feminism as “Password”: Re-Thinking the “Possible” with Spinoza and Deleuze’. Hypatia 15, no. 2 (2000): 63.

19 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 26–39. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

20 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 31–32. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

21 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 33. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

22 Ulrik Schmidt. ‘The Socioaesthetics of Being Surrounded Ambient Sociality and Contemporary Movement-Space’. In Socioaesthetics : Ambience - Imaginary / Edited by Anders Michelsen, Frederik Tygstrup, 33–35. Social and Critical Theory 19, n.d.

23 Confino, Alon. ‘From “ Collective Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 198. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

24 Megill, Allan. ‘From “History, Memory, Identity”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 193. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

25 Samuel, Raphael. ‘From “Theaters of Memory”’. In The Collective Memory Reader, 261–64. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011.

26 Megill, op. cit.

27 Ernest Renan. Extract from from ‘What Is a Nation’. p. 83.

28 Svetlana Boym. ‘From “Nostalgia and Its Discontents”’. The Collective Memory Reader, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 452-57.

29 ibid.

30 ibid.

31 Peter Burke. ‘From “History as Social Memory”’. The Collective Memory Reader, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 188-92.

32 Megill, op. cit.

33 Renan, op. cit.

34 Megill, op. cit.

35 Megill, op. cit.